Political pop art: Beyond the Iron Curtain

- elaslater

- Aug 19, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 20, 2024

The Cold War cleaved the world in two – separating the Capitalist West from the Communist East (to generalise) and ultimately leading to a further destabilisation of geopolitics in the post-war period. As always, it was everyday civilians that suffered the consequences of politician’s mass power and control. Particularly beyond the Iron Curtain, where the KGB (Soviet secret police) and a large network of spies that kept the population wary of their neighbours, the oppression of freedom of speech directly led to the quashing of individuality of its citizens. As always, this also limited artistic creativity. Or so you would think. Even if the conventions of American Pop Art were not quite so strong in Eastern European art at the time, there are clear links between the Pop Art movement, and protest art that was being created in the USSR.

For example, Jerzy ‘Jurry’ Zieliński was a Polish artist with a clear hatred for the communist establishment, and how it oppressed national pride among Poles. His style directly contrasted what was taught in polish art academies at the time – utilising simple shapes and bold colours rather than academic post-impressionist painting styles. This clear breakaway from the methods he had been taught reflects his desire to rebel against the political context he was living through as it shows a clear rejection of the status quo, even on something considered as small as style and form. Zieliński also was member of ‘Neo Neo Neo’, a collective that criticised the lack of new thinking within the Polish art scene (no doubt due to political oppression). Combined, his activism - both through his art and through his involvement in ‘Neo Neo Neo’ - represent a desire to combat the overwhelming control the Soviets had over the lives of those in Eastern Europe. When art, (arguably one of the most freeing and hardest to control forms of creativity) begins to focus on protest, it encourages a critical view of the status quo. Undoubtedly, this was what Zieliński wanted.

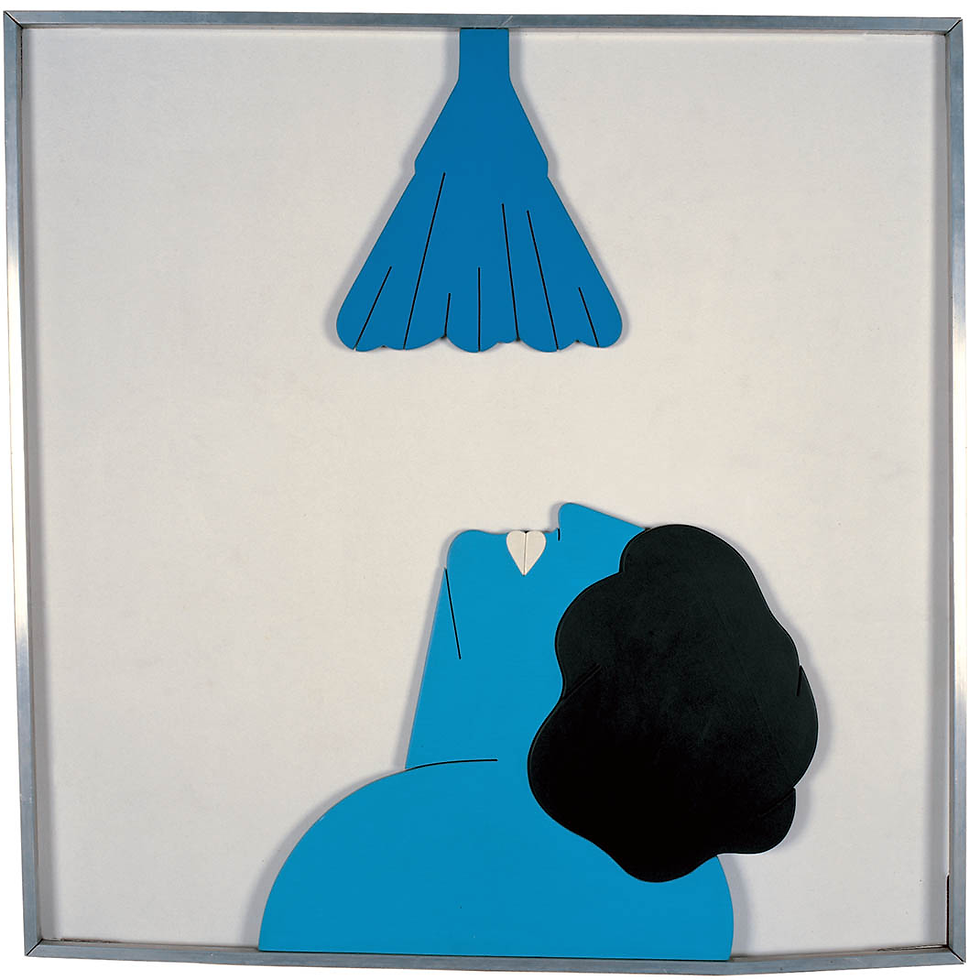

Similarly, Dušan Otašević, a painter from Belgrade in modern-day Serbia, is considered to have pioneered a specific Yugoslav variant of Pop Art. Pop Art itself was rising in popularity in the West, particularly in America as a form of rebellion to traditional art styles. In the East, it was emerging as a rebellion from the regime and a way to draw parallels with the freedom in the West. While in America, pop art was heavily influenced by their capitalist state (often featuring goods, such as the iconic Cambells soup can), Slavic pop artists such as Otašević instead explored the USSRs struggling economy and overwhelming lack of consumer goods. By making ‘Western’ art Yugoslav, Otašević criticises the constraints placed on the freedom of Soviet citizens, even down to the type of art they could make, and instead places emphasis on the freedom to create art without limits in the West. By association, this of course extends to other freedoms enjoyed by those in the West that seemed unthinkable to those in the USSR.

But why is their work so significant? Put simply, because it exists. For those in the USSR, living through mass censorship and control of movement, lifestyle and freedoms, exploring your creativity through Western styles just wasn’t done. You want to make capitalist art? Too bad. People were killed for less. But, against all odds, we have art. And the art that we do have is weirdly American, considering it came from behind the Iron Curtain. This proves not only that artists were craving a breakaway from the traditional forms of artwork that they had been taught at art academies (like artists in America), but that they also looked to the West for inspiration. Its a cry for help, and a demand for change.

The point is, both of these artists had similar experiences, underwent similar forced control of their lives and freedoms, and ultimately rebelled through the only medium they knew. Art. Particularly, Pop Art. A newly emerging medium that reflected a change in the future of artwork and the constraints of what

you could create, and in the west reflected their flourishing free-market economy. In the east, where their economy was significantly less flourishing and the common man was left with less, Pop Art took on a new meaning. It wasn’t a representation of a change in the art scene, as it was in America. It was a representation of a desire for change, and the possibility of a better existence. The fact that the works of Dušan Otašević and Jerzy Zieliński exist is only proof of the enduring resistance of the Soviet people through any means possible, and an overwhelming desire to preserve their own culture.

Artworks pictured in order:

'The Smile or Thirty Years, Ha Ha Ha' by Jerzy Zieliński (1974)

'Applause' by Dušan Otašević (1967 - 2011)

'Goracy', (Hot) by Jerzy Zieliński (1968)

'Venus is Rinsing the Detergent Foam' by Dušan Otašević (1970)

Comments